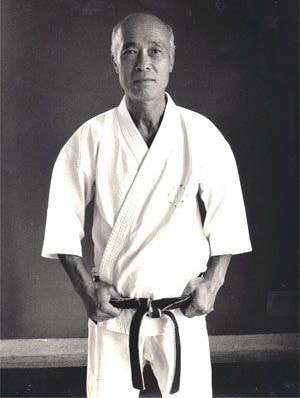

The Founder of Wado in the UK & Europe

Tatsuo Suzuki 8th Dan Hanshi (1928-2011). Principle Sensei of the European Wado-ryu and the Chief Instructor for the United Kingdom Karate-do Wado-Kai. Suzuki-Tatsuo was born in Yokohama, Japan on the 27th April 1928. At 10 years old the family moved to Ushigome, Tokyo. At 13 they moved to Hamamatsu, his father’s original hometown.

His first style of Karate was Shito-ryu, at his high school. He started training at the Yokohama YMCA Wado-ryu Karate Club at the age of 17 under a student of Hironori-Ohtsuka, known as Kimura Sensei. Kimura was reputed to be the best student of Ohtsuka Sensei at that time. Suzuki Sensei trained regularly with Ohtsuka Sensei, as Ohtsuka Sensei visited the YMCA regularly.

Suzuki Sensei was awarded 5th Dan in 1951 for outstanding courage and ability. Suzuki Sensei held the title of ‘Hanshi’, which was awarded to him by a member of the Emperor Higashikuni family. In 1963, with the assistance of Arakawa Sensei and Takashima Sensei, Suzuki Sensei introduced Wado-ryu Karate to the UK, Europe and the USA. In 1965 he returned to England where he set up his European Headquarters. Amongst his titles he held 2nd Dan in Tenshin-Koryu Bo-jutsu and 1st Dan in Judo. He has also studied Zen doctrine with the high priests, Genpo-Yamamoto and Soyen-Nakagawa.

I was born in Yokohama, Japan in 1928. My father was a fun loving man who enjoyed life to the full. He loved to cook, and owned a large restaurant. It was often hired by businessmen and local dignitaries for private parties where they could eat, drink and be entertained by Geisha.

This all came to and end when we were forced to move to the country to avoid American bombers during the war. School life was hard, and senior students would often beat the younger children for no reason. It was very militaristic, we looked upon our teachers as gods; I suppose it was just like the Samurai and his Lord.

I desperately wanted to become a soldier but was too young. I tried to join a naval academy but was rejected due to an eye problem. In hindsight I was actually quite lucky as they were all training to be Kamikaze pilots but at the time I was devastated. I was raised with the Bushido code, to die for my emperor and country would have been a great honour.

It was while at school that I had my first taste of martial arts. We practiced Kendo every day. When I was 14 years old I met one of my school friend’s older brothers. He had studied Wado Ryu Karate while at university; from then on whenever he came home I would ask him to teach me. Eventually he agreed; it was all fighting – nothing technical.

After the war my family moved back to Yokohama. The Americans were occupying Japan and despite my hatred of them I ended up working at one of their army bases as a cleaner. Government propaganda had turned Americans into demons that killed our men and raped our women. Through working at the base I came to realise that this was a lie. At that time food was scarce, we were living off insects and rice. The Americans gave us food, chocolate and of course Coca Cola. I loved it; it was all I ever wanted to drink; now I hate the stuff!

I decided to learn English and went to the local YMCA where they held classes. Once there I discovered that they also taught Karate. I knew that it was Karate that I wanted to do and soon forgot about learning English. The instructor there was a man called Mr. Kimura. He was one of Professor Ohtsuka’s best students. Professor Ohtsuka was the founder of Wado Ryu Karate.

The Americans had banned all martial arts so we had to call Karate, Japanese boxing. I trained at the YMCA for about 6 months before we had to move on. We would train wherever we could, in gardens or fields, in the rain and snow, anywhere the American’s could not find us. Kimura was a very intelligent man with a very sharp technique. He was a 5th Dan at the time the highest grade in Japan.

I was fascinated by the way of the warrior and the samurai code. I read books on Budo, Bushido and Hagkure. As a boy I dreamt of being a samurai hero. After the war we were not allowed swords, so I looked for a martial art without weapons. In Judo it was always the big guy who won, but Karate was different. With speed, timing and good spirit I could defeat any opponent large or small.

Post-war Japan saw the Japanese people embrace everything American, baseball, coke, Elvis. I wanted to give the world something Japanese. I decided to become a great martial artist so I could teach the world about the Japanese spirit.

When I first started I was only training four hours a day that eventually increased to 10. Everyone thought I was crazy but I believed that to be the best I had to work longer and harder than anyone else. I would train in a shrine garden near my home until well into the early hours of the morning. By wearing my gi (the white Karate outfit) I inadvertently started a rumour of a ghost who stalked the shrine at night.

At the end of every year I would go up to a temple in the mountains for two weeks. There I would train every day from morning until night, only stopping for one small meal. To eat any more would make me sick. My day would start with a run, followed by Zen meditation. After that I would practice my punching by extinguishing a candle flame with just the force of my punch. Next I would work on my kicks by wearing iron boots. This built strength and speed. My favourite technique was the sokuto (side kick), Ohtsuka Sensei would tell students, if you wish to practice sokuto go see Mr. Suzuki.

That would be followed by three hours of fighting with my fellow students. By the end we would be physically exhausted. To end the day I would practice kata (set moves against imaginary attackers). I would perform each kata three times. When finished my body would feel great all the days aches and pains gone.

I would travel to Tokyo several times a week to train with Ohtsuka Sensei. He was a truly great man. Away from Karate he was a gentleman but inside the dojo he was like a true samurai. He would train with us as well as teach us. Many of his senior black belts had returned from the war, they were tough both physically and mentally. The fighting in those lessons was extremely hard.

In the old days fighting was different than it is today. There were no rules, any technique was allowed; kicks to the groin, strikes to the eyes or throat. Contests would be organised between the various universities. We would visit with a team of 10 fighters – to us they were the enemy, especially if they practiced a different style. Nowadays most styles fight pretty much the same way, but back then I could tell a person’s style of Karate from the way he fought. Shotokan fighters were very stiff and liked lots of room, whereas Goju Ryu liked to get in close – Wado Ryu would be somewhere in between.

The home crowd would be crying for blood and would often try to hit us with sticks or whatever they could lay their hands on. The senior students would referee but would rarely stop a fight unless it looked as if one of us was about to be killed. We would end up fighting on blood-soaked floors. No pads or guards were worn, it was all bare fists. Many people lost teeth or broke noses or other bones. Eventually the heads of all the styles got together to devise competition rules. They were concerned that potential students were being put off.

In 1963 I and two other students traveled the world demonstrating Wado Ryu Karate. This resulted in offers from several countries to come and teach. I narrowed it down to either Britain or America, as English was the only other language that I could speak. I was offered a sponsorship deal by some American businessmen, but a leading Shotokan instructor, Ohshima, was already teaching there so I declined.

I moved to England in January 1965. It was hard to settle at first. My English was very basic; I had to take a Japanese/English phrase book to lessons to try to explain my teaching. As I was the on

ly Japanese instructor in England everyone wanted me to teach them. Demands on my time were so great that I had no time to do any other work.

At first I thought that it would be difficult to teach westerners an oriental martial art. Back in Japan I had been told that Westerners could not move as we did because they sat on chairs as opposed to the floor, as a result they had no hip power obviously this was wrong.

I missed Japan; I was living in a bed-sit that would get so cold that it would be impossible to sleep. I would have to train to warm-up before going to bed. There were no Japanese shops and I longed to eat some Japanese food.

The whole profile of martial arts in the west took a great leap forward during the so-called ‘Bruce Lee boom’. I found myself on TV and in the papers all of the time. This kind of attention always attracts people out to prove themselves. None of them were any good. There was once a Hungarian man who claimed to be one of Bruce Lee’s top students, after one month’s training with him, a student would be able to beat any opponent. I was outraged by this claim so I contacted the paper that ran the article and challenged him to a fight under any rules that he cared to set. I waited but heard nothing, so eventually I rang them back. He had told them that he had already beaten me and saw no reason to fight me again. I laughed; he was obviously scared to face me man-to-man. Over the years I have proved myself and gained people’s respect. I still like a good fight though. Most days I spar with Kevin, an instructor at my London dojo, it helps to keep me sharp.

I had several jobs while I lived in Japan, which sometimes required me to use Karate, including nightclub bouncer and bodyguard. There was often friction with the yakuza (Japanese gangsters). I once found myself up against a local yakuza gang. I was alone but there were about 20 of them. I backed up to a wall and picked up a large rock. If I stepped forward they would move back, if I moved back then they would move forward. Luckily one of my friends was passing by on his way to buy some sake and saw what was happening. He run back to our house and returned with help. Even though there were only 5 us of against 20 of them, the yakuza were terrified. One of their gang had recently lost an eye in a fight with a Karate man. I dropped the leader with a blow to the groin and knocked out another one who came at me with a knife. The rest of them eventually managed to run off. I realised that I had lost my university cap – I would be in serious trouble if it were to be found by the police. I searched everywhere for it and eventually found it under the body of a yakuza. The next day I scoured the papers for reports of a dead body but found nothing – I guess no one was seriously hurt.

Fear with regards to fighting can be overcome by mental training. It’s a vital aspect of Karate training. It is important when fighting to have a strong spirit and a brave heart. When attacked you must never be scared or startled. You must believe in yourself this is difficult to achieve. A famous samurai was once asked what he would do if he were attacked in the street. He replied that he would move towards his attacker so that he could not strike down with his sword. To back off or freeze would mean death. I would often go to monasteries to learn Zen meditation from the monks. A samurai would not fear death before battle; this was the state of mind that I aimed to reach. I am always careful though, and will never change in believing that I am invincible. You must be wise and careful.

These days too many people stop training once they pass 2nd or 3rd Dan, they don’t realise that belts are not important. Grades mean nothing; all that matters is to train hard. Many people call themselves 10th or even 12th Dan, but most of them are rubbish.

When I was awarded my 5th Dan no university student had ever been graded so high. I did not want this and asked Ohtsuka Sensei not to give it to me but he insisted. It was the same for my 8th Dan. Over the years I have been offered 10th Dan but refused it. It would mean nothing to me, the only man worthy of giving me a grade was Ohtsuka Sensei and he is dead.

It is still important for me to train regularly. It can be difficult though, demands on my time have increased tremendously over the past few years. As well as my own training I teach twice a week at my London dojo. I am also the head of a very large Karate federation, the Wado International Karate-Do Federation (W.I.K.F); I travel extensively both here and abroad holding courses for my members.

I have sensed a definite shift towards the more traditional aspects of Karate recently. There has been an increased attendance from non-W.I.K.F students at my courses. This pleases me because I feel very strongly that all clubs should have a thorough grounding in the traditional aspects of their style, even if their bias is towards sport Karate.

As a response to this I have re-organised my federation in the UK. Large clubs and organisations can now affiliate with the W.I.K.F and enjoy all the benefits of our courses, competition (both in the UK and abroad) and our guidance, but still keep much of their financial independence. I feel now that it’s time for all Wado groups to work closer together whether it is through courses or competition. The fact that we all practice Wado Ryu Karate means that we are all brothers and sisters.

It is with the deepest sadness and regret that we must inform you of the passing of Suzuki Sensei in the early hours of Tuesday 12th July 2011. Let us remember his life and not his passing. Eleni Labiri Suzuki.